Jewish Genetic Diseases

FD is a genetic disease caused by mutations in the IKBKAP gene. One in 30 Ashkenazi Jews has the mutation, which is found on chromosome 9. Despite the fact that there is no known cure for FD, treatments focus on controlling symptoms and preventing complications. These treatments include special feeding techniques, respiratory care, and orthopedic management.

Canavan disease is a hereditary disease passed on through an autosomal recessive pattern. While it affects people of any ethnicity, it is most common in Ashkenazi Jews. Tests include a CT/MRI scan to look for deterioration of myelin in the brain and a urine/blood/cerebrospinal fluid test to check for increased levels of N-acetyl-L-aspartate (NAA). Aspartoacylase levels are also measured.

In its most severe form, the condition causes degeneration of the central nervous system. Affected infants usually develop delayed motor skills and miss developmental milestones. They tend to have larger heads and weak muscles, and their symptoms can progress to swallowing problems and seizures. Sadly, children with Canavan disease often die during childhood, but some sufferers live into adolescence and early adulthood.

Currently, there is no cure for Canavan disease. It is caused by a gene mutation in the canavan gene. However, researchers are developing strategies to prevent or treat this disease in the future. The use of gene therapy is one method, with promising results. Another approach involves replacing the mutated gene with a functional counterpart.

The prevalence of Canavan disease in the general population is unknown. It is estimated to occur in one in every 6,400 to 1 in every thirteen-thousand Ashkenazi Jews. However, the disease is rare in individuals of other ethnic groups. Regardless of its severity, individuals with Canavan disease should seek medical care as soon as possible.

Treatment for Canavan disease focuses on reducing the symptoms and improving the quality of life for affected individuals. Treatment plans vary based on the severity of the symptoms and the child’s needs. Early intervention and physical therapy are often helpful in improving posture and communication skills. If seizures occur, patients may also benefit from anti-convulsants.

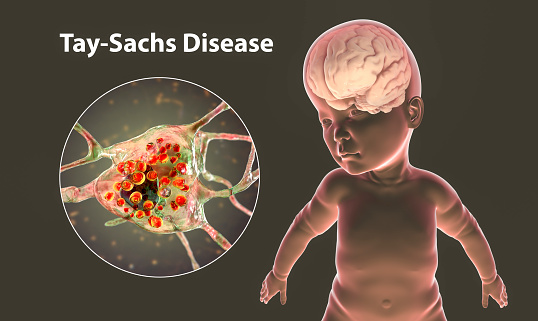

Tay-Sachs disease

People of Jewish descent are more likely to develop Tay-Sachs disease than other groups. It is a genetic disorder caused by a mutation in an enzyme called hexosaminidase A. This enzyme breaks down lipids in the spinal cord and brain. These lipids are toxic and can damage the nervous system. There is no cure for Tay-Sachs, but the disease can be prevented.

Symptoms of Tay-Sachs disease can be mild or severe. The disease affects the nervous system, and causes a slow, progressive decline in mental function. Those with the disorder may experience loss of vision, hearing, and motor skills. Some people who have the disease can suffer a short life span.

People who are carriers of Tay-Sachs disease can identify their carrier status by getting a simple blood test. The enzyme assay will measure the level of Hex-A in the blood. In carriers, the enzyme is present in lower amounts than those without it. DNA-based carrier testing looks for specific mutations in the Hex-A gene, which was discovered in 1985. Current tests can detect about 95 percent of carriers with Jewish ancestry, and 60 percent in the general population.

People who carry the disease are at high risk for developing the disease. The incidence of TSD is 1 in 360 000 births. The disease is more common in Ashkenazi Jews than other groups. In fact, one in every eighty-nine Ashkenazi families has the disease.

Screening for Tay-Sachs disease at NYU Medical Center follows an established model. Patients are educated so they can make an informed decision about their genetic tests. This approach has resulted in patients choosing to undergo screening for three autosomal recessive diseases, including Tay-Sachs disease. In addition to genetic counseling, the screening process is also available for patients who are at risk of passing down genetic disorders.

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is based on genetics, and many Ashkenazi and European Jews are carriers. The risk of contracting the disease is one in four, and it is often fatal. Genetic tests are available to determine if you have this disorder.

Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive disease, which means that both parents carry the disease gene. Each pregnancy increases the risk of having an affected child by 25 percent. Ashkenazi Jews have carrier frequencies of one in thirty for Tay-Sachs disease, one in 57 for Canavan disease, and one in 15 for Gaucher disease. While the latter is usually adult-onset and treated, the risk is still high among Ashkenazi Jews.

The incidence of cystic fibrosis varies greatly among different geographic areas and ethnic groups. Cystic fibrosis has been traced back to a genetic mutation on chromosome 7q31.2. The disease is hereditary, with both parents having the disease-causing gene, which causes the dysfunctional CFTR protein. In Ashkenazi Jews, one in 25 people have the mutation that causes cystic fibrosis.

There is no cure for this disease. However, treatments are available to control symptoms and prevent complications. These include special feeding techniques, respiratory care, and orthopedic management. As the severity of the disease varies from one person to another, genetic testing is recommended. If you think you are affected, you should consider genetic testing.

Cystic fibrosis is characterized by lipid accumulation in inappropriate locations in the body. This condition can result in brain damage and seizures. In Ashkenazi Jews, the disease is typically asymptomatic, though it can occur in adults.

Familial hyperinsulinism

Familial hyperinsulinism is characterized by severe hypoglycemia and can be fatal. Symptoms can begin as early as the newborn period and can progress throughout childhood. They may also lead to seizures, poor feeding, and breathing difficulties. Without treatment, familial hyperinsulinism can be fatal. Treatments can include glucose infusions and surgery to remove the pancreas.

Familial hyperinsulinism can be caused by mutations in several genes. A mutation in the ABCC8 gene accounts for about 45 percent of all cases. The overall incidence of familial hyperinsulinism is about one in 50,000. Ashkenazi Jews are more likely to be affected than other Jews.

Genetic testing is recommended for women. It can identify pregnancies at risk for passing genetic disorders to their children. Genetic counseling is also offered to women who have a high risk. Preconception testing is also a good option. This test can identify if either parent is a carrier.

The mutations responsible for familial hyperinsulinism have been identified. Researchers in Israel have identified a mutation in the sulfonylurea receptor gene (SUR1). The SUR1 gene is responsible for the abnormal pancreatic beta cell growth, resulting in familial hyperinsulinism. The disorder may be caused by a mutation in another gene, such as KCNJ11.

In a study conducted by Kukuvitis et al., four affected generations were analyzed. One case involved a French-Canadian kindred with documented hypoglycemia and 5 first cousins with an abnormal diazoxide response. Two of the patients had elevated insulin levels during hypoglycemia. The authors concluded that familial hyperinsulinism is autosomal dominant and may be hereditary.

The disease may manifest early in life, with symptoms appearing within weeks. Diagnosis of FHI requires close monitoring. Blood glucose levels should be measured frequently to detect symptomatic hypoglycemia. However, the determination of insulin concentrations is complicated, and sensitivity and specificity of commercial insulin assays vary. As a result, FHI may not be diagnosed in some individuals.

Joubert syndrome 2

Two scientists from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory have identified a genetic mutation responsible for the occurrence of Joubert syndrome in Ashkenazi Jews. These findings will be used to develop a screening program for this disease in the near future. According to the researchers, the disease is a chromosomal disorder characterized by developmental delays. The condition is more common among Ashkenazi Jews.

There are several types of Joubert syndrome, each with different clinical features. The disease can result in blindness and kidney failure. The first case was reported in 1997. In this case, an MRI revealed a “molar tooth-like structure” in the brain of the affected child. Until then, the condition was virtually unknown. Even today, diagnosis of the disease is a challenge.

Researchers have identified 20 genes that may be associated with the syndrome. Of these, six were responsible for two-thirds of cases. These genes include C5orf42, CC2D2A, AHI1, MKS1, and KIAA0586. Of the remaining families, two of these genes were not previously associated with JS.

Joubert syndrome is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder characterized by underdevelopment of the cerebral vermis. The cerebellum, or little brain, is a part of the hindbrain that controls balance and coordination. The disease is caused by a genetic mutation called TMEM216 that can occur in both parents. The disease affects approximately one in every 92 Ashkenazi Jews.

Although there is no cure for this disorder, healthcare providers may recommend treatments that can reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. Treatment depends on the type of symptoms and severity of the disease. Patients with the disorder may need to be monitored by neurologists, who specialize in the development of the cerebellar vermis and other areas of the body. Genetic counseling can also be helpful for families, since genetic counseling can help identify which relatives may be at risk for the disorder.